BIG PRAYER MUSEUM

World's First Global Living Museum & Advertising System

"All Catcher. Diversify Solution. Thanks for Watching." - A living system of meaning, movement & memory where brands and communities unite through purpose-driven engagement.

World's First Global Living Museum & Advertising System

"All Catcher. Diversify Solution. Thanks for Watching." - A living system of meaning, movement & memory where brands and communities unite through purpose-driven engagement.

Transform advertising into motion, meaning, and measurable engagement through our revolutionary four-pillar system:

Claim your message through branded apparel, media presence, and sensory installations. Your brand becomes part of the living experience.

Promote your cause or business through our global network. Multi-platform activation across physical and digital spaces.

Embody your values through movement and interactive participation. Authentic brand representation through experience.

Show up in our digital and global ecosystem. Continuous presence in our living museum and advertising network.

Join our ecosystem as a brand sponsor or individual participant with clear engagement tiers designed for maximum impact.

Companies & Organizations

Creators & Small Businesses

Our ecosystem seamlessly connects physical spaces, digital platforms, and sensory experiences for complete brand immersion.

Physical cultural space featuring interactive installations, sensory zones, and branded experiences that connect community with purpose.

Movement-based engagement platform that transforms advertising into physical interaction and wellness activation.

Sensory-driven gaming experiences where brands participate through taste, smell, sight, sound, and touch activations.

Online platform connecting all physical locations with virtual engagement zones, creating a worldwide participation network.

Wearable messaging system that turns clothing into interactive media, connecting participants across all platform touchpoints.

Real-time tracking of participant engagement across all sensory channels, providing measurable ROI for brand partners.

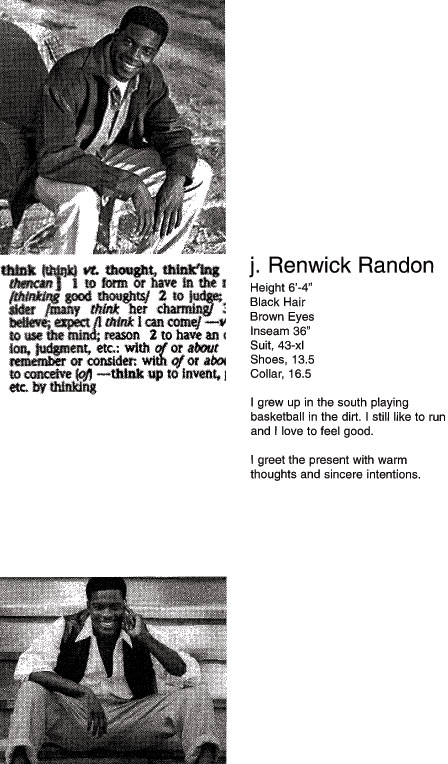

Founder of SoundWater.com | Geobody Sense Fitness | Big Prayer Museum

Team Prepare for Heaven on Earth

"To be a modern-day revolutionary as a Black man in America is to walk into the fire of misunderstanding and still rise with clarity."

I was born into a system that didn't expect my soul to shine — but I shine anyway. I don't just push back — I build forward.

I've learned that revolution isn't just what you fight against — it's what you stand for. I stand for healing. For rhythm. For sacred structure. For sound and water. For a system that teaches us to feel again, to see, to hear, to taste, to smell — to be fully human, fully alive, and spiritually grounded.

I created Geobody not as a product, but as a pathway — to realign with our senses, with our story, and with our responsibility. I built Big Prayer not as a museum of the past — but as a living system of the future, where we honor land, legacy, and our collective breath.

The revolution is inside-out. The healing is public. The score is love. And I'm still playing.

Born: The year they say man landed on the moon

Education: Graduate of one of the top research universities in the United States of America - School of Communication and Social Studies

Mission: Building systems that transform advertising into movement, meaning, and measurable engagement

We're not selling ad space — we're inviting presence, play, and purpose. Position your brand within a living, spiritual ecosystem where engagement becomes transformation.

"Thank you for supporting our apparel-endorsed player participation."